On our recent trip to China, we went on a culinary journey to the city of Yangzhou (Jiangsu Province), the birthplace of the popular Yang Chow Fried Rice (sometimes spelled “Young Chow Fried Rice”). It is also the birthplace of Huaiyang Cuisine, one of the four original cuisines of China.

In this Yangzhou Food Guide and Travelogue, I’d love to show you some of the most famous dishes from Yangzhou. Chinese people care a lot about food—to the point where each cuisine has its own museum! We visited and ate at the Museum of Huaiyang Cuisine, plus many more restaurants, so I have a lot to share.

A Food Trip

I went on this trip with Bill, my childhood friend Zhengli, and her husband. Bill and I wanted to visit Yangzhou specifically to learn more about Huaiyang Cuisine and taste the food in its birthplace.

I grew up mostly in Shanghai. While it is now a global metropolis with restaurants of all kinds, I grew up mainly on Shanghainese cuisine, known in Chinese as běnbāng cài (本帮菜), which translates to “local cuisine.”

It’s a mix of influences from the nearby provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang. Since Huaiyang cuisine originated in Jiangsu, I knew that it shared many common ingredients with the Shanghainese food I grew up with, and even famous dishes, like Yangchun Mian and Squirrel Fish in Sweet & Sour Sauce.

But as we search for more recipes to cover on the blog, and also seek to educate others more about the diversity of Chinese cuisine, I wanted to learn more.

This trip was purely about food. Zhengli and I sought out restaurants—famous spots, recommendations from friends, and smaller restaurants alike.

The only “touristy” thing we did was seeing the Slender West Lake (known as shòu xīhú – 瘦西湖 in Chinese), a scenic park that’s almost like an large arboretum or botanical garden.

The rest of the trip, we ate!

An Introduction to Huaiyang Cuisine

Originally, China had Four Great Cooking Traditions (sì dà càixì – 四大菜系):

- Huaiyang or Jiangsu Cuisine (淮扬菜)

- Yue or Cantonese Cuisine (粤菜)

- Lu or Shandong Cuisine (鲁菜)

- Chuan or Sichuan Cuisine (川菜)

It has since expanded into the Eight Great Cuisines of China, which includes the above cuisines, as well as Min (Fujian), Hui (Anhui), Xiang (Hunan), and Zhe (Zhejiang) cuisines.

Fun Fact!

Read more about the 8 great cuisines in detail to get an idea of the wide variety of dishes and culinary traditions in China! And these are just 8 of the biggest ones—there are even more to explore. I would love to visit all these cuisines’ museums, eat like the locals, and get the chance to get to know each one of them better!

Huaiyang cuisine comes from Jiangsu Province, located north of Shanghai on China’s eastern coast. Southern Jiangsu is also part of the fertile and prosperous Yangtze River Delta.

The cuisine is renowned for intricate knife skills, meticulous and artful preparations, the pursuit of delicate and refined flavors, and dishes that seek to highlight the main ingredient.

This region is also the main producer of some essential Chinese cooking ingredients, like soy sauce, cooking wine, and vinegar. For instance, you’ll often see the use of Zhenjiang black vinegar, which comes from Jiangsu’s city of Zhenjiang.

I love Huaiyang cuisine, so I made it my first stop, and I was determined to sample Huaiyang food (菜) in its birthplace.

Visiting the Museum of Huaiyang Cuisine

A visit to the Museum of Huaiyang Cuisine was a great way to start the trip. It is located inside the original home of the Qing Dynasty’s largest salt merchant, Lúshàoxù (卢绍绪). It’s an estate situated in Yangzhou near the ancient water canal (dà yùnhé – 大运河).

The estate is nine courtyards deep, with a large hall and rooms flanking both sides that separate each courtyard.

This beautifully preserved and restored private estate was constructed with gray brick, stone carvings, and carved wooden doors and windows.

It is enormous, covering over 5000 square meters (about 53,820 sq ft), with 130 rooms, completely surrounded by two-story brick security walls.

Exhibits in each large hall showcase the history of Huaiyang cuisine. Huaiyang dishes were first noted in the Qin Dynasty, the first dynasty of imperial China, lasting from 221-206 BCE. It was a well-established cuisine during the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

The exhibits highlighted some key dishes. The tantalizing displays included Wensi Tofu Soup (wénsī dòufu tāng – 文思豆腐), Lion’s Head in Clear Broth (qīngtāng shīzi tóu – 清汤狮子头), Salt Water Duck (yánshuǐ yā – 盐水鸭), Dongpo Braised Pork (dōng pō ròu – 东坡肉), and many more artfully plated delicacies that would definitely make you hungry.

Another exhibit showcased Huaiyang cuisine’s legendary knife skills using just the biggest cleaver you can imagine! Whether it’s julienning silken tofu, carving elegant flowers out of a radish, or grinding some pork, a large Chinese cleaver is the one knife chefs use to do every job.

The exhibits also honored some famous master chefs of Huaiyang Cuisine. It was nice to see a female chef was amongst the best. I bet there are a lot of good stories from her time!

As I mentioned in my post on the 8 Major Cuisines of China, Huaiyang cuisine is the main cuisine featured in Chinese State Dinners, probably due to its light and refined yet flavorful nature and impressive platings.

One exhibit showed a state dinner on full display (with some very well-made plastic food).

Here are the dishes shown! Dishes with an asterisk (*) next to them are Huaiyang cuisine dishes!

MENU SPOTLIGHT: A Typical Chinese State Dinner (featuring many Huaiyang dishes!)

4 Dim Sum Items (点心):

*Fried Rice Cake, zhà niángāo – 炸年糕

Mochi with Sweet Filling, àiwōwo – 艾窝窝

*Huang Qiao Sesame Pancake, huáng qiáo shāobǐng – 黄桥烧饼

*Huaiyang Soup Dumplings, huái yáng tāng bāo – 淮扬汤包

8 Cold Appetizers (冷菜):

Jellyfish with Sesame Oil, xiāng má hǎi zhé – 香麻海蛰

*Bamboo with Shrimp Roe Oil, xiā zǐ dōngsǔn – 虾籽冬笋

Cucumber Salad with Sizzling Oil, qiàng huángguā tiáo – 炝黄瓜条

Boneless Duck Feet with Wasabi Sauce, jièmò yā zhǎng – 芥末鸭掌

*Smoked Carp, sū kǎo jìyú – 酥烤鲫鱼

Stuffed Pork Stomach, luóhàn dù – 罗汉肚

*Zhenjiang Chilled Crystal Ham, zhènjiāng yáo ròu – 镇江肴肉

*Osmanthus Flavored Salt Water Duck, guìhuā yánshuǐ yā – 桂花盐水鸭

7 Hot Dishes (热菜):

*Yangzhou Crab Meat Lion’s Head, yángzhōu xiè ròu shī tóu – 扬州蟹肉狮头

*Happy Family, quánjiāfú – 全家福

*Braised Pork Belly, dōng pō ròu – 东坡肉

*Shredded Tofu in Chicken Broth, jītāng zhǔgàn sī – 鸡汤煮干丝

*Pot Stewed Chicken with Shiitake Mushroom, kǒumó guàn mèn jī – 口蘑罐焖鸡

*Jade Shrimp Stir-fry, qīng chǎo fěicuì xiā – 清炒翡翠虾

*Abalone and Four Treasures in Savory Sauce, bàoyú nóng zhī sì bǎo – 鲍鱼浓汁四宝

2 Desserts, 甜品:

*Pineapple Eight Treasures Sticky Rice – bōluó bābǎofàn – 菠萝八宝饭

Fruit Platter, shuǐguǒ pīnpán – 水果拼盘

Are you drooling yet? We were so hungry after seeing all these beautiful dishes (plastic or not, they looked pretty real), we then stepped into the museum restaurant and had ourselves a wonderful meal.

During the meal, we ordered Zhenjiang Chilled Crystal Ham, which is a braised/boiled and deboned meat in aspic. We also had a seasonal fava bean stir-fried with spring bamboo shoots and freshwater shrimp. It felt very much like home cooking.

The egg dish was stir-fried with toon sprouts (xiāngchūn – 香椿), which Bill has featured on the blog before in his version of Scrambled Eggs with Shrimp. Toon sprouts have a floral, peppery flavor, and are only available in springtime.

Of course, we had to order the famous Young Chow Fried Rice. The fish dish was a steamed shad (shí yú – 鲥鱼) with lots of wine and soy sauce. In Huaiyang cuisine, you may also see this fish steamed with sweet fermented rice (jiǔniàng – 酒酿) and thinly sliced ham for a sweet savory combination.

Later on in the post, I’ll talk more about my impressions of some of these famous dishes.

A Visit to the Wet Market

Visiting a local food market is a pastime that both Bill and I enjoy during travel. I find that it’s a great way to understand a local cuisine. I love seeing the ingredients and seasonal produce.

One seasonal item that we saw everywhere was called lú hāo (芦蒿), a wild vegetable.

You only eat the stems, cut into smaller pieces and made into cold tossed salads or stir-fried with small strips of meat. It tastes almost like a wild celery. I’ve never seen this vegetable outside of this region.

We also saw Chinese toon (which I mentioned eating in the museum restaurant), edible clover, fresh lily bulbs, and arrowhead root. Also in season were fava beans and water bamboo.

The region is full of freshwater lakes and rivers. Some of the aforementioned ingredients are grown in water, like the arrowhead root and water bamboo.

Other specialty ingredients from the area include certain freshwater fish (like the shad and freshwater puffer fish), freshwater shrimp, and giant freshwater snails!

There was a vendor processing these huge snails, trimming the ends to create an air pocket so the meat can be easily sucked out—no extra utensil required. It looked like she was doing a lot of them, perhaps to sell to a local restaurant.

Another big ingredient in the region is dried shrimp roe, made by salt-curing shrimp eggs. Dried Shrimp Roe is not often used outside of China. Its umami-rich flavor enhances an array of dishes from noodles to soups.

Shrimp roe has also made it into soy sauce, which is known as Shrimp Roe Soy Sauce (xiā zǐ jiàngyóu – 虾籽酱油). With my knowledge of Cantonese cuisine, I have only seen shrimp roe in egg noodles (xiā zǐ miàn – 虾籽面).

Striking up a conversation with the merchants is my specialty. I asked several vendors what they cook at home. All the restaurants serve similar traditional dishes, so I was wondering what home cooks are preparing. I can’t say I got very specific answers, but it was fun to chat nevertheless.

Yangzhou Food Guide: Famous Huaiyang Dishes

Basically, we tried as many dishes as we possibly could without wasting food. We managed to sample most of the signature dishes of the region. Here are some of the dishes we tried and our impressions of them!

1. Red Braised Puffer Fish (hóngshāo hétún yú – 红烧河豚鱼)

It seemed like every restaurant we went to had this dish on the menu. This is a freshwater puffer fish that comes from the Yangtze River, not the one that you may have seen or heard of in Japanese restaurants, which is an ocean fish.

The fish is red braised (cooked in soy sauce, wine, and some sugar), and though I was apprehensive to try it, I was reassured by my friend’s husband. He said, “méishì (没事)!” which means, “No problem!” So I ate it! I guess it doesn’t take much to convince me, haha.

The fish is a local delicacy, and its skin is the prize. I have to admit that it was very tasty. The meat was somewhat tight, similar to cooked tuna. Freshwater seafood has its own unique flavor—a very obvious umami. However, the texture of the skin wasn’t to my liking. It was thick and rubbery. I guess it makes sense, as the fish has the ability to puff up and expand. Bill and I weren’t too keen on the skin.

2. Lion’s Head in Clear Broth (qīngtāng shīzi tóu – 清汤狮子头)

The “Lion’s Heads” are actually baseball-sized meatballs. They’re rich, but also light and tender. This version is served in a flavorful clear broth, whereas the Lion’s Head Meatballs you may be familiar with from our recipe are braised in a sauce. That version is from Lu (Shandong) cuisine.

The meat mixture is actually 60% fat and only 40% lean meat! Perhaps what’s even more amazing is that the meat isn’t passed through a meat grinder. It’s actually hand-cut into tiny cubes—a testament to the chef’s knife skills.

This Huaiyang dish has always been mysterious to me. How can such a large ball of meat be so light and tender? And how can a meatball with such a large volume of pork fat not taste overly fatty? How is the fat not leaching out of the meatball?

Achieving that intensely flavored clear broth also takes great skill. Now that I have tasted it, it’s time to start working on the recipe. Can’t promise I’ll get it perfectly, but I’ll do my darndest.

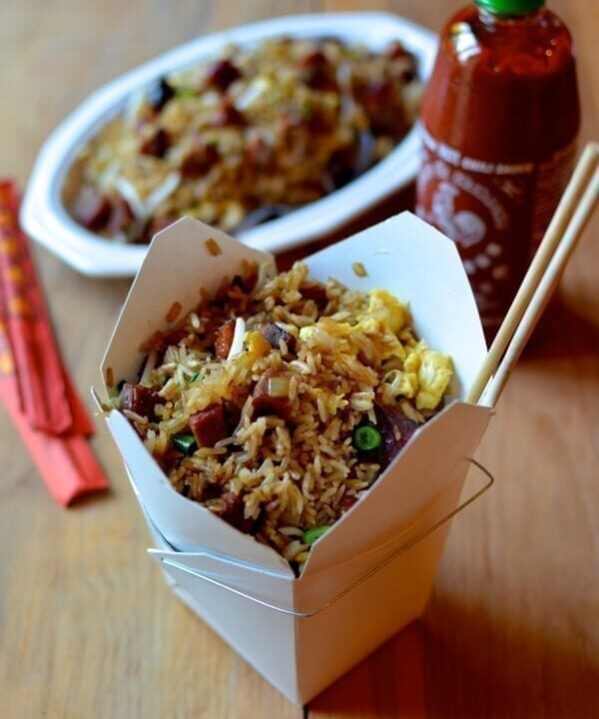

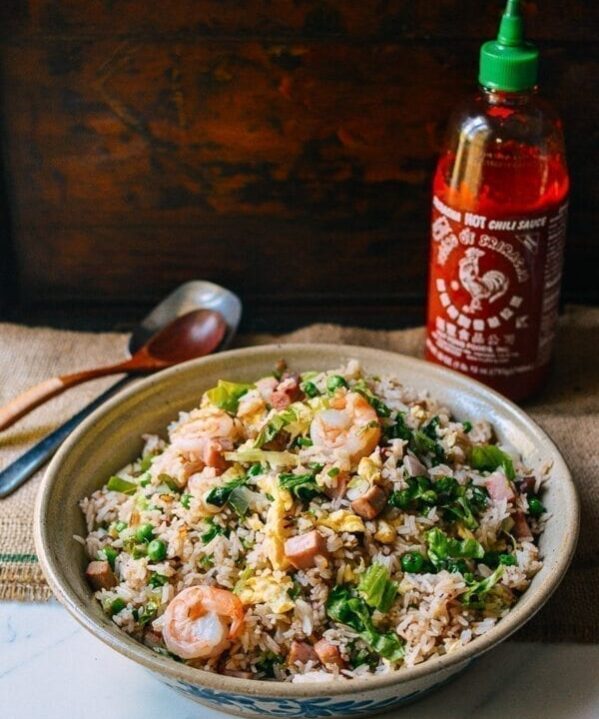

3. Young Chow Fried Rice (yángzhōu chǎofàn – 扬州炒饭)

This is perhaps the most well-known Huaiyang dish here in the U.S. First and foremost, this trip to Yangzhou has confirmed that Yang Chow Fried Rice is indeed one of Yangzhou’s signature dishes—not a made-up American Chinese take-out dish.

We all have seen and tasted many variations of Yang Chow Fried Rice, including our version, but now I can show you exactly what a version from Yangzhou looks like. The ingredients are rice, eggs, chicken, shrimp, ham, carrot, peas and scallions.

The rice grains are fluffy and glistening. The other ingredients are all finely diced to mimic the size of the rice grains. Even the small bits of ham in that rice are hand-diced with a Chinese cleaver!

The taste is balanced and harmonious. The fragrance of rice is the main character, with all the other ingredients playing a supporting role. A dash of salt brings all the players together, and the combination of colors makes the dish as visually appealing as it is tasty.

4. Wensi Tofu Soup (wénsī dòufu tāng – 文思豆腐汤)

Wensi (文思) is the cook who invented this delicate soup! The signature feature is the incredibly fine hair-like pieces of already delicate silken tofu, hand-sliced with insane precision. The soup stock is very flavorful and thickened to the consistency of egg drop soup, which allows the strands of tofu to stay suspended in the glossy liquid.

It takes a chef three to five years to master the skill of slicing the tofu (which is already extremely fragile) into such thin, equal size strands. This soup is a dish meant to impress the diner, and to showcase the skill of the chef who prepared it.

I myself was so impressed by those knife skills that I honestly remember more what the soup looked like than what it tasted like! Needless to say, I won’t be attempting this recipe. I would be too embarrassed to showcase the thickness of my tofu strands!

5. Squirrel Fish in Sweet and Sour Sauce (sōngshǔ yú – 松鼠魚)

I did not know that Squirrel Fish in Sweet and Sour Sauce is also one of their more famous dishes. I have mostly seen it in Shanghai. Who knew? That said, as Bill will tell you from developing his own version, this dish also takes some precision and knife skills.

The fish is essentially filleted and then cut into a cross-hatch pattern to create a lot of crispy surface area. Dredged, fried in such a way as to maintain its original shape, and then served with a glossy sweet and sour sauce on top, this is another dish that showcases the chef’s skill.

6. Yangzhou Morning Tea (zǎochá – 早茶)

Yangzhou is also famous for serving morning tea (早茶), just like the Cantonese tradition of Dim Sum brunch. Both involve having tea, but unlike Dim Sum, there were more cold dishes, wonton soups, and noodle soups. We went to the famous Qu Yuan Teahouse (qù yuán cháshè – 趣园茶社), known for its high-quality local specialties.

We ordered a pot of tea and sampled many local treats, like Three Ingredient Buns (sān dīng bāo – 三丁包), which are buns with small diced cubes of chicken, pork, and bamboo shoots, and Thousand Layer Oil Cake (qiān céng yóu gāo – 千层油糕), a lightly sweet yeasty cake with many thin layers and dried fruits on top. It turned out to be one of my favorite foods we tried on the trip!

This cake was featured at the Huaiyang Cuisine Museum:

Jade Siu Mai (fěicuì shāomai – 翡翠烧卖) featured leafy greens, a nice departure from the usual meat-filled ones. (See below, the real thing on the left, and the museum display on the right!)

We also sampled Soup-filled Steamed Dumplings (guàn tāng zhēng jiǎo – 灌汤蒸饺), which were kind of like soup dumplings, and Shrimp Roe Noodles (xiā zǐ bàn miàn – 虾籽拌面).

All the dishes were skillfully crafted and beautifully presented. I am really grateful to have tasted so many of them.

7. Tofu Shreds in Chicken Broth – (jītāng zhǔgàn sī – 鸡汤煮干丝)

This is a simple dish of shredded pressed tofu soaked in chicken broth. It doesn’t have the strongest flavor to it, making it characteristically Huaiyang in that nothing overpowers the flavor of the main ingredient.

It is one of the region’s Top 10 best known dishes. When we were traveling around the city, I noticed that literally every table was ordering it. I saw many restaurants keep a large pot of it on standby, so that they could quickly get orders to the table!

8. Salted Double Egg Yolk (gāoyóu shuāng huáng yādàn – 高邮双黄鸭蛋)

Gaoyou Double Yolk Duck Eggs are a local specialty. This particular breed of duck is known for prolific egg laying, and in particular, laying eggs with twin yolks. These duck eggs are salt cured, cracked open, sliced, and served on their own.

When it comes to salted duck eggs, the fattiness (or for lack of a better term, oiliness) of the yolk is key. There’s not much more to it than that! The eggs were served simply, cut into quarters, and enjoyed with the rest of the meal.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this travelogue from Yangzhou and this tour through some of the most famous Huaiyang dishes.

Do you have a favorite Huaiyang dish or connection to this cuisine? Do you have a recipe to request? Let us know in the comments!